The Women's Lectionary

Hi Friends! I have not been posting here very often lately because I have been hard at work on my book, The Women’s Lectionary, which will be published by Westminster John Knox Press this fall. I am so excited to share it with you! Here is part of the Introduction, where I tell the story of how this project came to be.

Some may be wondering why a Quaker is writing a lectionary. That’s a fair question. I am part of a tradition that, at least historically, completely disregards the liturgical calendar. In our traditional worship in the Religious Society of Friends, we sit in silence, waiting to hear the voice of God. We believe that God may lead anyone to speak, so we sit facing each other. We do not mark holidays because we believe that every day is sacred. For Friends who worship in the unprogrammed tradition, it does not matter what the occasion is—a holiday, a wedding, or a memorial—the order of worship is the same. We sit in silence, and people speak as led. So, I do not seem like an obvious person to take on this project. And yet, I feel led by the Spirit to do so, and I will start by describing some of the influences that brought me here.

I was raised in the church, though not as a Quaker. My first experiences of church were as an infant. My parents attended the local Episcopal church in my hometown of Anchorage, Alaska. I was two months old when I played the baby Jesus in the Christmas pageant (by all accounts, I slept through the whole thing). When I was still a young child, my parents started attending a charismatic nondenominational church; this is the first church I remember. I remember singing, clapping, and being completely unable to speak in tongues. I attended Sonrise Christian School, a small, parent-driven private school in Anchorage, where most of the teachers came from Calvin College. I was involved in Calvinettes (now GEMS) and later youth group. I was in a Christian bubble for most of my childhood, with the good and bad that comes with being part of that kind of subculture.

Like many in my generation, I left the church of my childhood because the church I attended was unwilling to affirm the worth and dignity of LGBTQ+ people. Alaska was one of the first states to pass a “defense of marriage” state constitutional amendment. I was in public high school by that point, and I could not reconcile the good I saw in my queer friends with the messages I heard on Sunday mornings in my church. Although I continued attending with my family until I left for college, I no longer considered myself a Christian.

I left home at seventeen to attend a blessedly secular public university in California—and experienced culture shock in more ways than I could name. Although I was in the same country, Santa Cruz was an entirely different world than the one I grew up in. There I met people who did not go to church and were not conflicted about it, unlike my friends in Alaska. I did not attend church once while I was there, nor did I seek out any of the religious activities available on campus. I felt free, and I had no intention of going back.

The exception was a year I spent studying abroad in Santiago, Chile. That was my first experience spending an extended period of time in a predominantly Catholic country, and I found it fascinating. The entire city would shut down for Holy Week, and everyone I met was Catholic. It was a difficult year for me, in large part because a stranger sexually assaulted me halfway through the year. I felt lost, and I would spend Sunday mornings climbing to the top of the large hill near my apartment in Santiago, which had a statue of Mary at the peak. I would stay there, sitting with Mary, until I felt like I could walk back down. Occasionally, I would attend mass. One of my roommates’ mothers came to visit, and she asked me if I believed in God. I said that I did not know. Then she asked if I believed in Mary, and I assured her that I did. She said, “That’s fine then, as long as you believe in Mary!”

I found my way back to church when I was in law school a few years later. Law school was a strange place for me. I enjoyed the academic challenge, but I struggled with connecting with my classmates. I did not like the competition and posturing that law school seemed to bring out in people. My roommate felt similarly, so we did what we had learned to do as children: find a church. We agreed that we could not go back to the denominations we had grown up in (Southern Baptist, in her case), but we tried all the others that we could find. We almost ended up picking an Episcopal church and attended services there several times.

Then I went to visit my aunt and uncle for Thanksgiving. My parents had told them that I was looking for a church, and they suggested that I try a Quaker church. They had attended a local Quaker church for several years, and they thought it might be a good fit for me. When I got home, I looked online for a Quaker church, and found Freedom Friends Church. I went with my roommate, and I felt immediately at home. Freedom Friends Church was a semi-programmed Quaker worship, with singing, prayers, and an extended period of silence. I loved all of it, and I kept going on my own after my roommate moved away. I felt that I had found a place where I could be myself, without others telling me how to be or what to believe. My church supported me when I came out as queer. I went deeper and deeper into the silence in worship.

I moved to Seattle for work, and joined an unprogrammed Quaker meeting there. Unexpectedly, within my first year of working as a lawyer, I experienced an undeniable call to ministry. I began doing ministry and traveling among Friends, and I became well known for blogging and organizing Quaker events. Even more strangely, I felt called to preach. I would pray in the United Church of Christ church across the street from the court where I worked and envision myself in the pulpit. I felt led to attend a two-year program called The School of the Spirit, with residencies four times a year in North Carolina. People kept asking me if I planned to go to seminary and I would say no, I already had a graduate degree. Then one night, it became clear to me and my support committee that I was led to attend seminary. I planned to go to Candler School of Theology, a United Methodist seminary in Atlanta, Ga. Just months before I left, my church recorded me as a minister, the Quaker version of ordination.

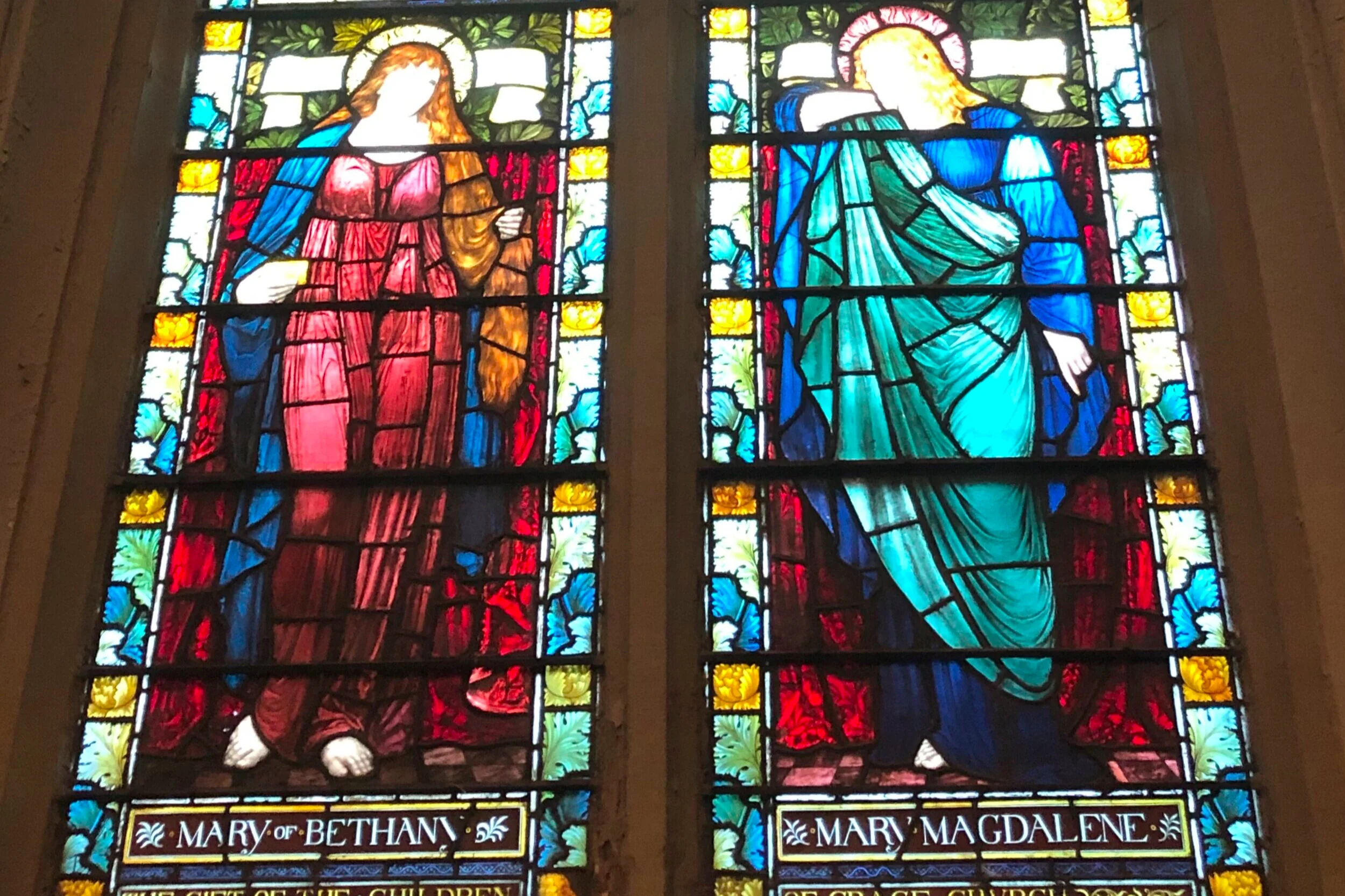

At Candler, I studied with professors from many traditions, including Lutheran, Catholic, Presbyterian, and Baptist, as well as United Methodist. After graduation, I stayed connected to Candler as part of the teaching team for professor Ted Smith’s Introduction to Preaching course, and I founded a church called Church of Mary Magdalene, where women preached. Church of Mary Magdalene came out of a dream I had of preaching for women, who moved their chairs up to hear what I had to say. This was my first experience with weekly preaching, and I enjoyed the challenge. But I felt torn between wanting to use the Revised Common Lectionary—with the community and resources that accompany it—and wanting to preach about women. I was talking about this in the car with my partner Troy on Thanksgiving of 2017. Troy turned to me and said, “Well, why don’t you write your own lectionary?”

This idea captured my imagination, and I spent the next several days putting together a draft of a lectionary based on women in the Bible and feminine images of God. I met with Ted Smith to discuss the idea, and he encouraged me to write commentaries for each of the passages. I used this lectionary for a year at Church of Mary Magdalene, exegeting the texts to preach on them and then turning the sermons into commentaries. In addition to preaching at Church of Mary Magdalene, I preached once a month at a local retirement community vespers service. One evening after the service, a woman came up to thank me for my message; she said that she had never heard a sermon from Mary’s perspective before. “The women are there in the Bible,” she mused, “But no one ever talks about them!” Incrementally, the project grew.

In Introduction to Preaching, Ted Smith uses the metaphor of “hybrid vigor” to describe the teaching team. Each person on the teaching team has experience in at least two traditions. Many, like me, come from a number of different traditions. The idea behind hybrid vigor is that this mixing of traditions makes us stronger preachers—we bring the best of multiple denominations to our study and delivery of the message. I believe this to be true, based on my own experiences and having observed students preach in the class for four years now. We can be deeply rooted in one tradition, while appreciating and borrowing from others. As you read the commentaries, you will see the influence of each of the traditions I have encountered, and I am sure you will bring your own as well.

Would you like more updates on The Women’s Lectionary? Subscribe to my email list!